WELCOME TO MY BLOG.

I've always had an interest in gardens and in the natural world. I soon realized that these were more than just flowers to me, but people, places, pictures, history, thoughts...

Starting from a detail seen during one of my visits, unexpected worlds come out, sometimes turned to the past, others to the future.

Travel in a Garden invites you to discover them.

Starting from a detail seen during one of my visits, unexpected worlds come out, sometimes turned to the past, others to the future.

Travel in a Garden invites you to discover them.

Monday, December 23, 2019

Saturday, December 21, 2019

The Christmas Dinner Table

The Christmas Dinner Table

This design is intended to appropriately decorate the Christmas Dinner Table, and consists of a Wreath which is composed of pieces of Fine-leaved Ivy, Leaves of Variegated Box, Holly, Sprays of Mistletoe, intermixed with Small Apples, Winter Cherries &c. &c. Nos 1 are for Lamps; Nos. 2, Plants; Nos. 3, Fruits; Nos. 4, Confectionery, Nos. 5 are intended to be Glass Dishes, large size, for cut Flowers; Nos. 6 are Glass Tubes eight inches high; Nos. 7 Glass Tubes four inches high; and Nos. 8 are Small Low Glass Dishes - all to be filled with Cut Flowers.

Floral Designs for the Table; Directions for Its Ornamentation with Leaves, Flowers & Fruit. John Perkins. London, Wyman & Sons, 1877

Saturday, December 14, 2019

Flowers and Figurines

Tuesday, December 10, 2019

'Still-life with a pineapple': a painting by Ilya Mashkov and a book by John Claudius Loudon.

Pineapple had been introduced to Russia in the 18th century. Special greenhouses and ingenious techniques were developed to cultivate this exotic fruit in the long and harsh Russian winters.

The first hothouses were dug below the freezing level of the soil (around 2 meters) and covered with a glazed structure made of logs. Many skilled gardeners were required to take care of the growth and fruiting of the plants.

By the end of the 18th century, pineapple were not only cultivated in noble estates but also in peasant farms and expensive Russian pineapples were successfully exported to European countries. Around eighty new varieties of pineapples were bred in Russia where their cultivation continued until the middle of the 19th century, when cheaper importations from tropical countries and a more expensive labour force made it less profitable.

The first hothouses were dug below the freezing level of the soil (around 2 meters) and covered with a glazed structure made of logs. Many skilled gardeners were required to take care of the growth and fruiting of the plants.

By the end of the 18th century, pineapple were not only cultivated in noble estates but also in peasant farms and expensive Russian pineapples were successfully exported to European countries. Around eighty new varieties of pineapples were bred in Russia where their cultivation continued until the middle of the 19th century, when cheaper importations from tropical countries and a more expensive labour force made it less profitable.

During his travel on the Continent between 1813 and 1814, John Claudius Loudon (1783-1823), the great English botanist, garden designer, horticulturalist and author, observed how "... the Pine Apple is cultivated most extensively in Russia; it occurs but seldom in France or Germany; and only in a few gardens in Italy." In his book The Different Modes of Cultivating the Pineapple from Its Introduction into Europe to the Late Improvements of T. A. Knight Esq. published in 1822, he reported about:

"Culture of the Pine Apple in Russia.

The Pine Apple is extensively cultivated in the imperial gardens in the neighbourhood of Petersburg and Moscow, and also in those of a few of the greatest nobility and mercantile men adjoining those cities. Nothing can be more wonderful than to contemplate the resources by which this plant, requiring not less than from 50 to 70 degrees of heat at all times of the year, is preserved in existence through a winter of seven months, during the whole of which the ground is covered with snow, and Fahrenheit's thermometer, often for weeks together, at 20 degrees below Zero.

The head gardeners of the emperor, and the great nobles of Russia, are, for the greater part, Britons; and the sort of houses they erect, and the mode of culture they follow, is as nearly as circumstances will admit, those of Speechly or Nicol.

The culture of the grape is, to a certain extent, combined with that of the Pine Apple; the former is trained on the rafters, and the latter grown in a pit, surrounded by flues and a path. In addition to the flues, many of the fruiting-houses have stoves built in them, on the German construction, which are used in the most severe weather. Sometimes there is a double roof of glass; but more generally the roof, ends, and fronts, are covered with boards; which not only prevents the weight of sudden falls of snow from breaking the glass, but by admitting of a coating of snow over them, prevents, in a considerable degree, the internal heat from escaping. This covering, or a covering of matts or canvass, as practised near Moscow, and from which the snow is raked off as fast as it falls, is sometimes kept on night and day for three months together. The plants being all the while in a dormant state, it is remarkable how little they suffer. ...

There are some German gardeners in Russia, who cultivate the Pine Apple in pits as in Holland; and crowns and suckers are forwarded in this way by them, and also by the British gardeners settled in that country."

Loudon does not mention that the 'golden pineapple', considered a vegetable related to cabbage at first, was served at the noble tables fried and stewed as side dish for meat and game, marinated in vinegar in interesting salads or as a drink fermented in barrels.

Pineapple cultivation gained new interest at the beginning of the 20th century but ceased after 1917.

Loudon does not mention that the 'golden pineapple', considered a vegetable related to cabbage at first, was served at the noble tables fried and stewed as side dish for meat and game, marinated in vinegar in interesting salads or as a drink fermented in barrels.

Pineapple cultivation gained new interest at the beginning of the 20th century but ceased after 1917.

Photos:

painting: Still life with a pineapple Original Title: Натюрморт с ананасом.

Ilya Mashkov (1881-1944), 1910, Oil on canvas

https://www.wikiart.org/

"Mr Loudon’s Improved Pinery"; pineapple greenhouse, 1810.

Engraving by J. Pass, showing a system for growing pineapples advocated John Claudius Loudon (1783-1843). Illustration from ‘Encyclopaedia Londinensis, or, Universal Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Literature’ published in London, 1810-1829

https://thegardenstrust.blog

Further reading:

The Different Modes of Cultivating the Pine-Apple from its First Introduction into Europe to the Late Improvements of T.A. Knight, Esq., by a Member of the Horticultural Society, London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Browns, 1822.

Sunday, December 1, 2019

In autunno, 1882. Filippo Carcano (1840-1914)

The skyline of Milan is seen beyond a row of potted flowers and plants arranged on the parapet of a balcony under a cloudy sky.

At the end of the Nineteenth century, the centuries-old spires of the Duomo are flanked by a soaring smoking chimney and a belt of houses and factories that will soon take the place of the golden trees and fields in the outskirts of the city.

A nasturtium runs along the balcony next to a bergenia, with its fleshy and shiny leaves. A red carnation is tied to three sticks and three vases with red flowers, possibly hibiscuses, are close together. Moss covers the vase of a tropical plant with large light green leaves next to a begonia with a warm copper textured foliage and tiny white flowers. The lanceolate tips of a variegated plant suggest the presence of other vases on the floor of the balcony.

Filippo Carcano was an Italian painter who lived and worked in Milan and is considered an important figure in the school of Lombard Naturalism.

Painting from:

Filippo Carcano

Saturday, November 23, 2019

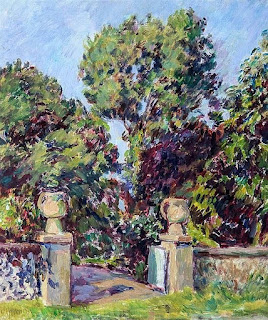

Before the Garden: Charleston, East Sussex

Charleston in East Sussex was the home of Duncan Grant (1885-1978) and Vanessa Bell (1879-1961) from 1916.

Charleston in East Sussex was the home of Duncan Grant (1885-1978) and Vanessa Bell (1879-1961) from 1916.A low stone and flint wall runs along the road edging the garden. A closed-boarded wooden gate is flanked by square pillars topped by two concrete urns cast by Quentin Bell in 1952.

The gate opens onto a gravelled courtyard with the "lovely, very solid and simple" (VB) house to the left, and the lawn and a quiet pond to the right.

Beyond there is a coloured, overflowing cottage garden where statues scattered among flowers and fruit trees prove the intense artistic and creative spirit that permeated every aspect of their life.

Photos:

TravelinaGarden, Charleston August 2016

B&W photo from: A Hunting Glimpse into a lost past at Charleston, SussexLife 2016

Painting: Duncan Grant "Ornamental urns in Charleston garden", oil on canvas, 1972

Further reading:

Charleston a Bloomsbury house & garden, Quentin Bell & Virginia Nicholson, Frances Lincoln Limited 1997

Sunday, November 17, 2019

To answer your questions... Julia Artico on making hay sculptures.

The simple, familiar shapes and unexpected material of her sculptures touch something deep, invite you to stop and smell the fragrance of hay, to touch it and breathe, to listen in silence and look with more open eyes and a new smile.

I asked Julia a few questions to better understand her work and she kindly answered me.

Julia Artico: I started working hay by chance about 15 years ago. Due to a mistake, I had no electricity; therefore, I could not do the carpentry workshop for which I had been hired. I had to quickly find a second-best with the material available at the time. It so happened that they had mown the grass that day, so I had wonderful and fragrant hay to play and let play. The first hay labs were born.

TravelinaGarden: Your works invite people to get closer to nature with the pure and dreamy eyes of a child who sees a mountain in a stone. Hay is the scent of summer but also the hard work and hardship of rural life. What would you like to convey with your work? How is it perceived by people who live and work in the countryside?

JA: The purpose of my work has always been to act as a bridge between human and nature, to draw attention to simple things and forgotten gestures.

Luckily for me, my installations are also very appreciated by those who live in the countryside and have more direct contact with land. As a matter of fact, I believe it is because they converse with the amazement of the inner child in us.

TravelinaGarden: How do you deal with the inevitable decay of your works whose duration is more limited compared to, for example, marble statues?

JA: Mine is the beauty of impermanence, a glance beyond. Every day, the transience of life and of phenomena teaches us: the beginning already contains the end.

TravelinaGarden: Is the manual aspect important in your creative process? Could you tell us something about the practical aspect of your creative process?

JA: Being able to bring what comes to my mind into matter IS EVERYTHING!! I could not think about the creative act without taking into account the manual aspect, feasibility and my inevitable limits.

I can tell you the genesis of my last installation: "Vita Nova", made for Villa Barbaro at Maser, Treviso, a Palladian villa frescoed by Veronese, a pearl of rare beauty. [see photo below]

I started from a pentad of words developed with the help of Salvatore Lavecchia and from the opera Bees by Rudolf Steiner. Hence the idea of inserting a hypothetical Vitruvian man made of rye, the element of bees, into a hexagon of metal. Daniele Barbaro, who commissioned the Villa, translated and commented on Vitruvio's work. In addition to draw attention to the problem of bees, the installation is a wish to all of us to push towards a more respectful balance with the kingdoms of nature.

I usually make my own hay because it needs to be mown by scythe, as it used to be, and dried in the sun. Clearly, even the most propitious moments for its storage are taken into account, otherwise the good result of my work could be compromised. In fact, I use only natural hay, without treatments.

I make scale models to understand if the idea works, and then I enlarge them. Inside structures can be either full or empty and I use both wood and metal to make them, depending on the customer and on their use. Hay is assembled with very fine strings that contain and shape it.

TravelinaGarden: How do you 'preserve' your work?

JA: I keep away from pouring rains empty works, which I can carry without difficulty. Full works that are not transportable come back to nature in a couple of years, depending on their volume.

TravelinaGarden: What are your projects for the near future?

JA: I am working on projects related to bees and their well-being.

In the chaos of our everyday life, we don't to pay attention to these little beings. They would deserve to no longer be exploited, because it must be remembered that honey is their livelihood and not our food. We subtract honey and give them sugar in return, which make them sick.

But we know that man does not understand, does not listen and thinks only to his immediate advantage. Bees and pollinators are on this earth to pollinate the food we eat, and if we continue like this, there will be no future for our children.

Thank you Julia and hope to see you soon!

"At the end of the summer,...the peasants proceed to the higher pastures, and there they mow and carefully scrape together...those short and strong-scented grasses which grow so slowly and blossom so late upon the higher mountains. This hay has a peculiar and very refined quality. It is chiefly composed of strong herbs, such as arnica and gentian, and is greatly prized by the peasants."

from 'Hay Hauling on the Alpine Snow', p. 248

Our Life in the Swiss Highlands, by John Addington Symonds and his daughter Margaret, 1892

|

Tra Cielo Terra e Acqua - Oltre il Paesaggio mistico

|

|

Mothers - Blachernitisse Contemporanee

|

|

The Game of the Goose - Orticolario, Como, 2018 |

|

Vita Nova - Casa di Vita - Armonia del Tempo

|

Photos:

TravelinaGarden, see captions for locations and dates of the different installations

Link:

JULIA ARTICO - CREATIVITA' NATURALE

******************************

Julia Artico: Ho iniziato a lavorare il fieno per caso circa 15 anni fa. A causa di un disguido, non avevo la corrente elettrica e quindi non potevo fare il laboratorio di falegnameria per cui ero stata ingaggiata, ho dovuto ripiegare in tutta fretta sul materiale disponibile al momento. Il caso ha voluto che quel giorno avessero tagliato l’erba, quindi ho avuto a disposizione del meraviglioso e profumatissimo fieno per giocare e far giocare, sono nati così i primi laboratori del fieno.

TravelinaGarden: I tuoi lavori invitano ad avvicinarsi alla natura con gli occhi puri e sognanti di un bambino che vede una montagna in un sasso. Il fieno e' profumo di estate ma anche la fatica e durezza della vita contadina. Cosa vorresti trasmettere con i tuoi lavori? Come sono percepiti dalle persone che vivono e lavorano in campagna?

JA: Da sempre la finalità del mio lavoro è quello di fare da ponte tra l’umano e la natura, riportare l’attenzione sulle cose semplici e sui gesti dimenticati.

Per mia fortuna le mie installazioni sono molto apprezzate anche da chi vive in campagna ed ha un contatto più diretto con la terra. Credo che sia dovuto al fatto che in realtà dialogano con ilo stupore del bambino interiore che è in noi.

TravelinaGarden: Come ti poni rispetto all'inevitabile decadimento dei tuoi lavori la cui durata e' più limitata se paragonata, ad esempio, a delle statue di marmo?

Julia Artico: La mia è la bellezza dell’impermanenza, lo sguardo che va oltre. La transitorietà della vita e dei fenomeni ce lo insegna tutti i giorni l’inizio contiene già la fine.

TravelinaGarden: E' importante nel tuo processo creativo l'aspetto manuale? Ci puoi raccontare qualcosa dell'aspetto pratico del processo creativo?

Julia Artico: Riuscire a portare nella materia quello che mi passa per la mente E’ TUTTO!! Non potrei pensare all’atto creativo senza tener conto dell’aspetto manuale, della fattibilità e dei miei inevitabili limiti.

Posso raccontarti la genesi della mia ultima installazione “Vita Nova” realizzata a Villa Barbaro a Maser, TV. Villa Palladiana affrescata dal Veronese una perla di rara bellezza. [vedi foto]

Sono partita da una pentade di parole sviluppate con l’aiuto di Salvatore Lavecchia e dall’opera API di Rudolf Steiner, da qui l’idea di inserire un ipotetico uomo di Vitruvio realizzato in segale, l’elemento delle api, in un esagono di metallo. Daniele Barbaro, che fece costruire la villa, aveva tradotto e commentato il lavoro di Vitruvio.

L’installazione oltre a riportare l’attenzione sulla problematica delle api vuol anche essere un augurio a tutti noi che ci spinga verso un equilibrio più rispettoso con i regni di natura.

Sono solita fare da me il fieno che utilizzo per i miei lavori perché ha bisogno di essere tagliato a falce come una volta ed asciugato al sole. Chiaramente si tiene conto anche dei momenti più propizi per la sua conservazione, che diversamente pregiudicherebbero il buon risultato dell’opera, infatti non uso che fieno naturale senza trattamenti.

Per capire se l’idea può funzionare realizzo dei modelli in scala che poi vado ad ingrandire. Le strutture possono essere sia piene che vuote internamente e per realizzarle posso usare sia legno che metallo, dipende tutto dal committente e dall’uso che se ne deve fare. Il fieno viene assemblato con lo spago molto fine che lo contiene e lo modella.

TravelinaGarden: Come 'conservi' le tue opere?

Le opere che conservo al riparo dalle piogge battenti sono quelle vuote dentro che posso trasportare senza difficoltà. Quelle piene e non trasportabili rientrano in natura in un paio d’anni, dipende dai volumi.

TravelinaGarden: Quali sono i tuoi progetti per il futuro?

Julia Artico: Sto lavorando a dei progetti collegati alle api e al loro benessere. Nel caos della vita di ogni giorno non si riesce a portare attenzione su questi piccoli esseri che meriterebbero di non essere più sfruttati , perché va ricordato il miele è il loro sostentamento e non il nostro cibo . Noi sottraiamo il miele e diamo in cambio lo zucchero che le fa ammalare.

Ma si sa l’uomo non capisce, non ascolta e pensa solo al suo torna conto immediato. Le api e gli impollinatori sono su questa terra per impollinare il cibo che noi mangiamo, se continuiamo così non ci sarà un futuro per i nostri figli.

Tuesday, October 29, 2019

Words in pictures: Autumn Landscapes by Milton Avery (1885-1965)

Fall in Vermont, 1935. Oil on canvas, 32 × 40 inches. Collection of The Milton and Sally Avery Arts Foundation. © 2016 The Milton Avery Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Autumn Landscape, circa 1939. Oil on canvas. 61x91,4cm. Private collection.

Autumn in the Rockies, 1948.

Hint of Autumn, 1954. Oil on canvas. 136.5 x 86.4 cm. Private collection.

Sunday, May 26, 2019

Words in pictures: Lilacs in Russia

|

| Pavlovsk - May 2019 |

Lilacs and Forget-Me-Not, 1905. Igor Grabar (1871-1960)

Lilac, 1906. Natal'ja Sergeevna Gončarova (1881-1962)

Lilac, 1915. Konstantin Alekseevič Korovin (1861-1939)

Lilacs, 1940-50. Aleksandr Aleksandrovich Deĭneka (1899-1969)

Photos: TravelinaGarden, St. Petersburg - Moscow, May 2019

Sunday, April 21, 2019

Birds Nest, Apple Blossom and Primroses.

[...] the only master I longed for would not teach, i.e. old William Hunt, whose work will live for ever, as it is absolutely true to nature. We used to see a good deal of him at Hastings, where he generally passed his winters, living in a small house almost on the beach under the East Cliff, where he made most delicious little pencil-sketches of boats and fishermen. I can see him now, looking up with his funny great smiling head, and long gray hair, above the poor dwarfish figure, and his pretty wife, with her dainty little openwork stockings and shoes, trying to drag him off for a proper walk on the parade with her daughter and niece, where he looked entirely out of character. I remember "That Boy," too, whom Hunt taught to be anything he chose as model, blowing the hot pudding, fighting the wasp, or taking the physic; the apple-blossoms and birds'-nests, with their exquisite mosses and ivy-leaved backgrounds, were found in the hedges and gardens about Hastings.

From Recollections of a happy life, being the autobiography of Marianne North, by North, Marianne, (1830-1890), 1892.

Birds Nest, Apple Blossom and Primroses, William Henry Hunt (1790-1864), Watercolour, bodycolour and gum, on paper

© Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery

Saturday, April 20, 2019

Words in pictures: apple blossoms

Victoria Fantin-Latour, neé Dubourg (1840-1926)

Gustave Courbet (1819-1877)

Branche de pommier en fleurs, 1871.

Henri Fantin-Latour (1836-1904)

Fleurs de pommier, 1873. Oil on canvas

Martin J. Heade (1819-1904)

Hummingbird and Apple Blossoms, 1875. Oil on canvas

Kreyder Alexis Joseph, 1839-1912

Natalia Goncharova (1881-1962)

Still life with apple blossom, oil on canvas

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)